I felt like an insect. For two hours I had been driving into black when suddenly my headlights were washed out by an overwhelming light. I approached the illumination with a captivation I had been long deprived of on the road thus far. I brainstormed the possibilities of the source – a stadium, perhaps, or an airport.

“The state prison,” my father concluded.

I’m not sure if the wave of coldness I felt while passing was self-inflicted or not, but it was undeniably noticeable. Upon further inspection I could make out a long, white building surrounded by a sole barbed wire fence. There was a watchtower in the center, sitting much higher on the horizon than the institution below. By the time I glanced back to the road, I had been staring long enough to create lightning when I blinked. I determined that the inhabitants there must live in perpetual daytime. I wondered if that bothered them. I wondered what they felt like. I wondered who they were.

It’s easy to categorize a person based on what their statistics or track record look like, but the idealist in me wants to believe that a human can only be judged by their conscience. It’s extremely discomforting to think of my life as being defined by numbers and listed accomplishments rather than moral inclination and makeup of the heart. Some would argue, with substantial physical proof, that those who commit crime can automatically be deemed immoral. I have to challenge that notion. Working at the animal shelter led me to question my previous judgments.

Orientation day was eye-opening. I went in expecting a vast majority of the volunteers to be either teenagers in need of service hours or lonely middle-aged women with a particular fondness of orphaned animals. The handout we were given had two choices at the top: volunteer or community worker. I looked around and realized that I was in the minority; a largely unshaven, less-than-clean-cut audience surrounded me, all circling the second choice.

On my first volunteer day, I worked with a boy slightly under my age. He knew the place surprisingly well, and somehow I understood that he had been a regular worker there to fulfill a juvenile delinquent sentence. I distanced myself a bit, assuming that he and I had too vast of differences to get along. Since he had already done most of the cleaning by the time I arrived, we were out of tasks to complete within an hour. We stood around awkwardly, aware of the other’s presence but unsure of what to do.

“Wanna see the puppies?” he finally asked, headed for the dog room. I followed him, and we came up to a cage marked “Rabies Quarantine.” Nobody questioned our entrance.

We sat on the cage floor for at least an hour playing with a group of terrier puppies. He became particularly fond of them. He raved about how he wanted one and how jealous he was since they seemed to prefer me to him. We spent the remainder of the time joking around and choosing and naming one for him.

I never saw him again, and never found out what he did wrong to be ordered service, but the puppies were gone by my next visit. In reality, he wasn’t a serious criminal, but he still led me to wonder what other personalities I had missed out on due to preconceived notions of the “villainous.”

In volunteering regularly, I came across many contradictory sights. Guys with sideways baseball caps and chains spilling out of their sagging pockets suddenly became weak when witnessing the crying kittens in the back room. Girls with a plethora of eyeliner, studded belts and ripped jeans crowded around the cage of baby rabbits with unnatural smiles plastered on their faces. Once I saw a teenage couple cleaning litter boxes for a few hours. As I left, they were sitting on the bench outside taking a smoke.

Seeing these people out of their felonious element was somewhat disturbing. People tend to like things black and white, but my lines were being blurred with all kinds of gray. I wondered if all accused criminals could be so humane.

I was being shown around the shelter one day by an older community worker.

“Here’s the washing station,” he pointed at the row of sinks in the back. “Down there’s the dog room, the cats are up at the front. Food is right here, water bowls are over there, and litter boxes at the bottom of this shelf.” I was impressed by the knowledge these people had of the place. One could almost be convinced that they actually liked the work. He led me outside, where rows of cages littered the cemented ground. An odd-looking black box sat in the center of the pavement with a small metal door.

“And here’s where they incinerate the ones that don’t make it,” he smirked. In that moment I felt the same cold I had felt in passing the prison that night.

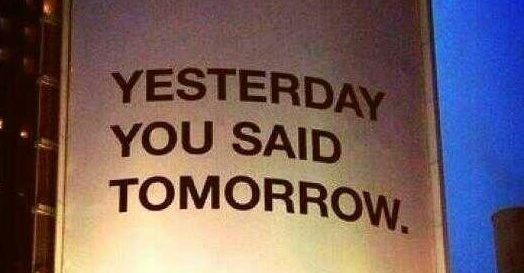

It’s easy to follow the light, I think. It’s easy to blind yourself. There’s always going to be a level of distance between do-gooders and those with a questionable agenda, but I think it’s nearly impossible for even a criminal to completely abandon their humanity. At the end of the day, we are not statistics, salary, accomplishments or records. We are blood, flesh, heart and mind; and that makes us all more similar than different.